Blog |

2/23/25 cont.

I'm continuing with this morning's topic, having done a bit more research. This concerns an 1827 novel, published in New York, entitled "A Voyage to the Moon: With Some Account of the Manners and Customs, Science and Philosophy, of the People of Morosofia, and Other Lunarians," signed "Joseph Atterley." It is attributed to a Virginian, Professor George Tucker. I learned that while this attribution was decided upon by scholarly consensus in the mid-20th century, nonetheless, Tucker personally claimed authorship. Keep in mind all this is preliminary. I don't know how far I'll try to pursue this one--but it's instructive as a model.

There was a book published in 2018, having been edited by Prof. Paul C. Gutjah. It's way too expensive for me, and I was going to order it through interlibrary loan, but my local public library's website seems to be down. Fortunately it wasn't necessary, because I found the relevant portion, i.e., Guthajr's introduction, online. I wrote him as well; but whether he'll write back is another matter. Very, very few of them do. In this case, I'm telling him about a significant discovery--Mathew Franklin Whittier's 1831 four-part series, being very similar to the 1827 novel. This is something that scholars appear to have entirely overlooked--and one would think that I deserve a response, if only to allow me to share this historical discovery.

But I'll tell you what I've concluded--these people are actually afraid of the truth. They are afraid of evidence which disproves or disrupts their own scholarly work; and then their excuse for turning a blind eye to it, is skepticism.

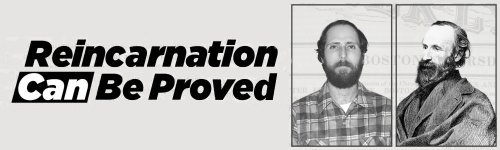

It so happens that Dr. Gutjah has, in his private collection, a copy of this book, with the author's personal inscription to a colleague. It is signed "The Author," but the handwriting seems to match Tucker's own. They were both professors at the University of Virginia, which was headed up at that time by its founder, Thomas Jefferson.

There is a possible rationale for Tucker using a pseudonym, "Joseph Atterly," for this publication and only for this publication--and that is that Jefferson disapproved of novels, and that the book is satirical, such that Tucker might have been afraid to be associated with it. It's a weak rationale, in my opinion, but it's somewhat plausible. In my observation, either authors used pseudonyms, or they didn't. By that I mean, not "branding," like "Mark Twain," but real pseudonyms designed to maintain complete anonymity. Either authors, like Mathew's brother John Greenleaf Whittier, signed everything they published so as to build their reputation and put their authorial mark on their work, or like Mathew, they published everything anonymously.

Where you have someone who signed everything except one work, I suspect plagiarism--which is to say, falsely claiming authorship of an anonymous work.

I've discovered this over a dozen times. If you dare publish an exceptional work anonymously, in the 19th century, sure enough someone is going to say it's theirs. They might just brag privately to their friends and family, but then it gets out sooner or later. I can flat-out prove several of these cases. Apparently, it was quite common in the 19th century.

So, here is the signed title page, as found in Prof. Gutjah's book:

Here's what I've found out by quizzing my AI copilot. Keep in mind that AI still hallucinates, and I haven't verified its responses, so take this with a grain of salt. This is the sort of thing I would want to run past the Professor, if he responds.

1) Dr. Tucker only ever used a pseudonym for this one novel.

2) Dr. Tucker did not typically employ satire. Only in this book did he do so.

3) His authorship--again, so far as I know, as I sit here, today--is based entirely on this inscription. In other words, it's believed to be his because he said so.

4) He was in favor of gradual elimination of slavery--as was Mathew, at this time, before Abby radicalized him--but unlike Mathew, he was not in favor of giving free blacks full citizenship. Both men were in favor of sending former slaves to Africa, but for different reasons: the Northerners like Mathew wanted to help them without triggering bloody rebellions; while the Southerners like Tucker wanted to get the free blacks out of the country.

Then there is the positive evidence suggesting Mathew Franklin Whittier's authorship. It's legion--I won't list it all, here, because to understand the full depth of it, you'd have to be as familiar with his legacy as I am. Suffice it to say, this is precisely in his style, it precisely reflects his personal philosophy (at least, what I have read of the book so far), and he was writing in this vein, and in this genre, from 1826 onward for several years. Furthermore, Mathew wrote something very, very similar four years after this was published, in 1831. Mathew always published anonymously, and he very frequently employed satire.

So other than the fact that Tucker claimed he wrote it, Mathew Franklin Whittier is a far more plausible author.

From what I have seen, Academia is absurdly naive in such matters. If someone--however implausibly--claims to have been the author of some work, they instantly swallow it hook, line and sinker. If one scholar publishes his opinion about the authorship of a work, assuming it to be true, this becomes HISTORICAL FACT for all time, and may not be questioned. Certainly not by any lay scholar such as myself.

But when you drill down into it, you find that this assumption of authorship has a very flimsy basis, indeed. Do you know on what basis scholars say that Margaret Fuller wrote the "F."-signed essay and reviews in "The Dial," and the "star"-signed reviews, essays and reports in the New York "Tribune"? Because she casually asserted it in private letters to friends and family, a handful of times. Do you know what Edgar Allan Poe's authorship of "The Raven" is based on? His having scooped the premiere by three days, stripping out the original pseudonym and replacing that with his own name. His authorship of that poem is utterly implausible. The deeper you look into it, the more absurd it is. But it is HISTORICAL TRUTH, indisputable FACT in Academia, because they have all signed off on it.

This is not scholarship--this is politics. Real scholarship would always vet these authorial claims. The scholars should start out skeptical, and then see what evidence there is to support it. They should assume, at the outset, that the claimant may be lying--because in the 19th century it was done flagrantly and routinely among a certain class of dishonorable writers.

Sincerely,

Stephen Sakellarios, M.S.